Eastern Promise (2024-2025)

Digital prints

Exhibited at Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou (2025) | ROSL, London (2025) | Saatchi Gallery, London (2025) | Fabrica Gallery, Brighton (2024)

Winner of LensCulture Critics’ Choice Award (2025) | ROSL Photography Award (2025)

Finalist for Kuala Lumpur International Photoawards (2024) | International Photography Exhibition 166 (2024)

Longlist for Aesthetica Art Prize (2025) | OD Photo Prize (2024)

Featured in European Photography Magazine 117/118 (2025)

Eastern Promise is a series that examines how colonial photography has shaped, and continues to shape, the perception and understanding of the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia. The work is based on late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century photographs taken by Western photographers of the Chinese community in colonial Malaya then. These images have now been digitally reproduced and stored in archives across Europe, alongside its physical copies.

Singapore was founded as a British trading post in 1819, and together with Penang and Malacca, became part of the Straits Settlements — a Crown Colony — in 1867. The city remained under British rule until the mid-twentieth century. During this time, with increased trade and movement between Europe and its colonies, Western photographers travelled to this region and established photo studios. Throughout history, the camera has often been wielded as a tool of violence, complicit in the perpetuation of oppressive narratives. Some of these photographs were intended as ethnographic studies, and were sold as souvenirs to European markets.

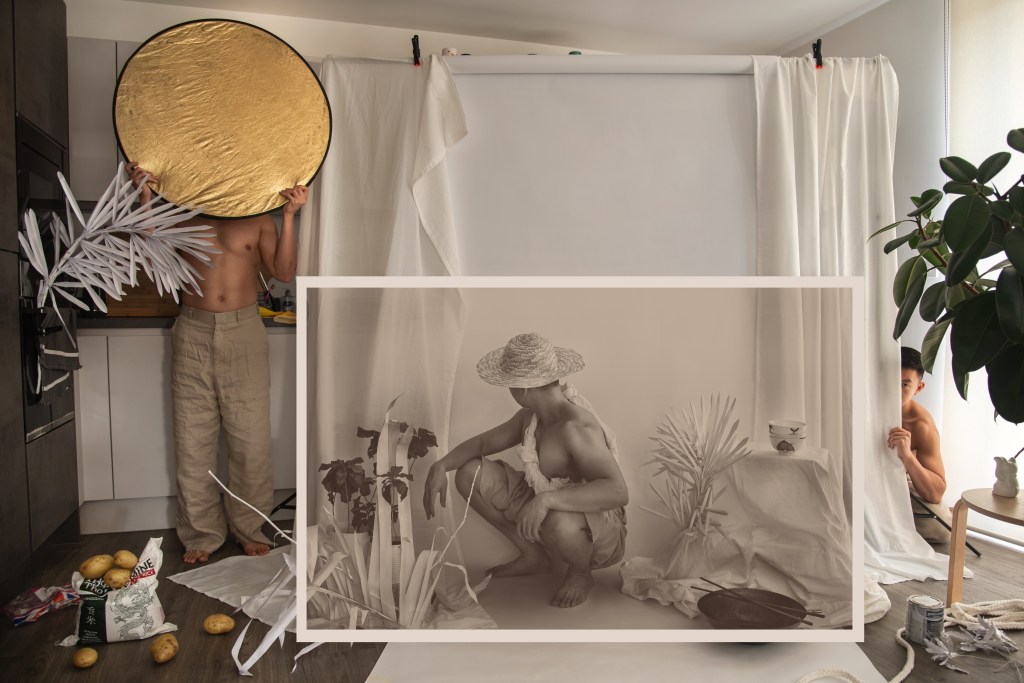

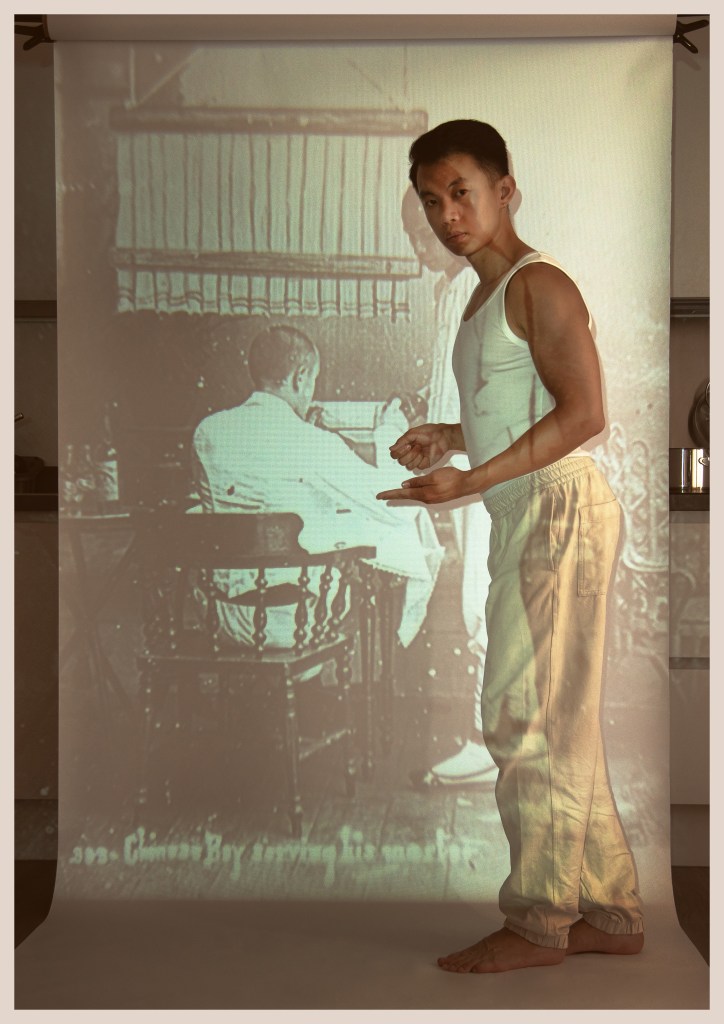

In looking at these historic images, I realised that certain tropes and patterns emerge from the photographs. Specific props, costumes, poses, and backdrops were used to contextualise and exoticise the Southeast Asian setting. Thus, to make these stereotypes and artificial constructions more apparent, I created my own props and costumes to extend the ‘colonial image’ beyond its frame. Through self-portraiture, I recreated these images within the domestic setting of my home in London.

Eastern Promise aims to interrogate how these images reinforced racial stereotypes and upheld imperial power. The resulting photographs unpack the artifices of the medium while critically examining the enduring legacies of colonialism.

Exhibition at Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, 2025

Photo: Zeng Yulin

Within the visual strata of colonial archives, the bodies of Chinese laborers were once fixed by the camera as ‘anthropological specimens’ — frontal, profile, standardized poses — serving the taxonomic gaze of empire. Through a dual-strategy photographic practice, Sean Cham excavates these colonized bodies from archival sediment and reactivates them within the private space of a contemporary London apartment.

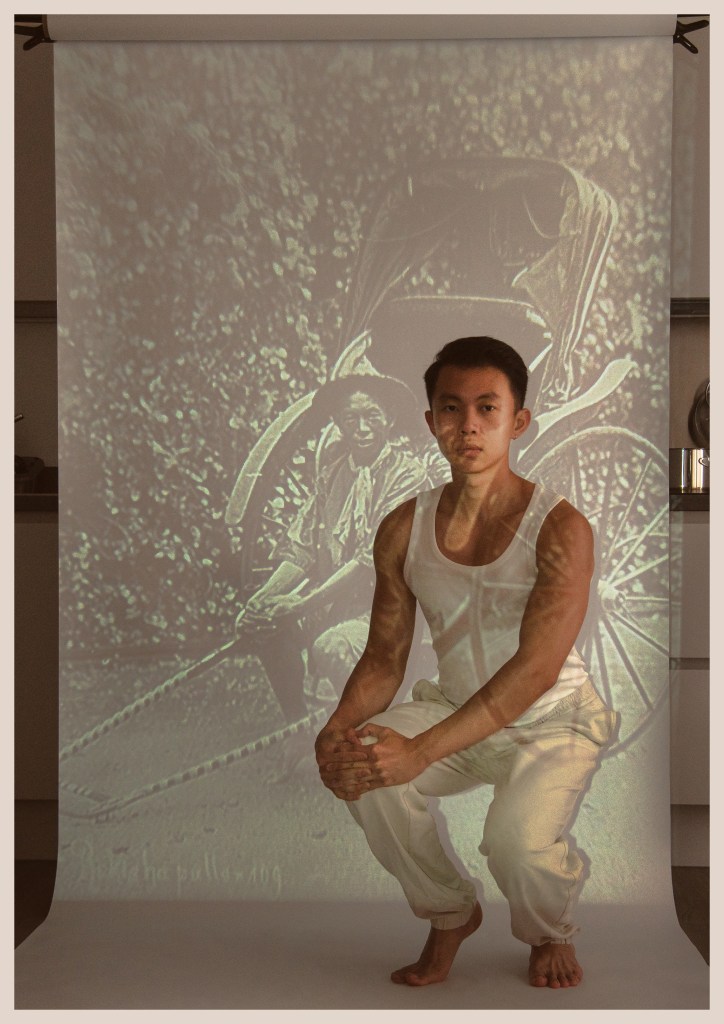

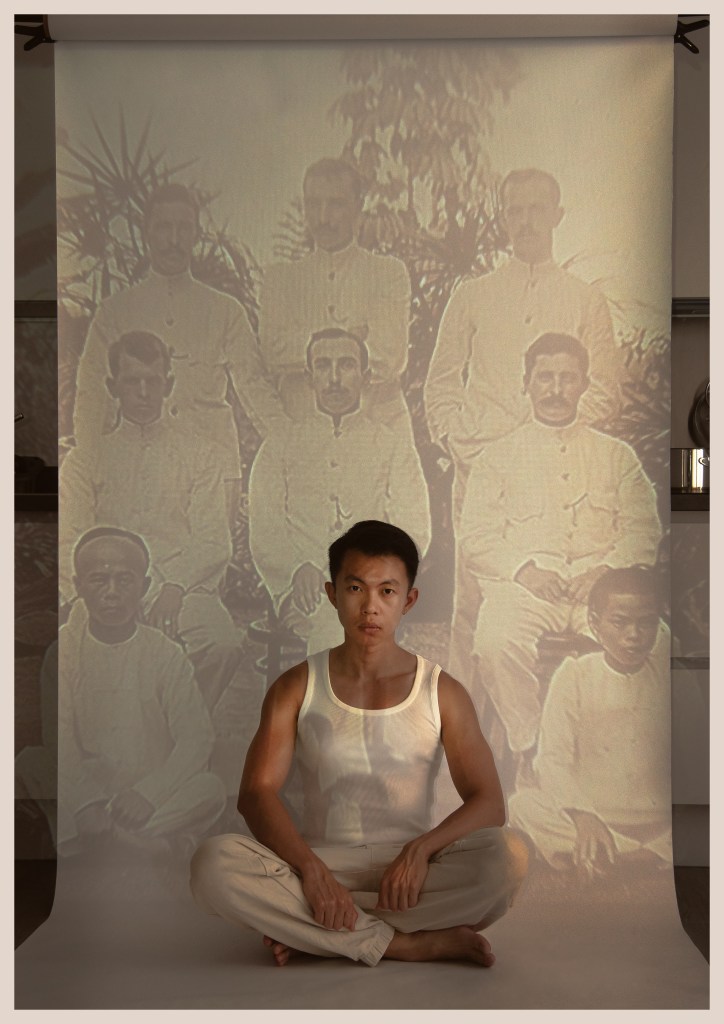

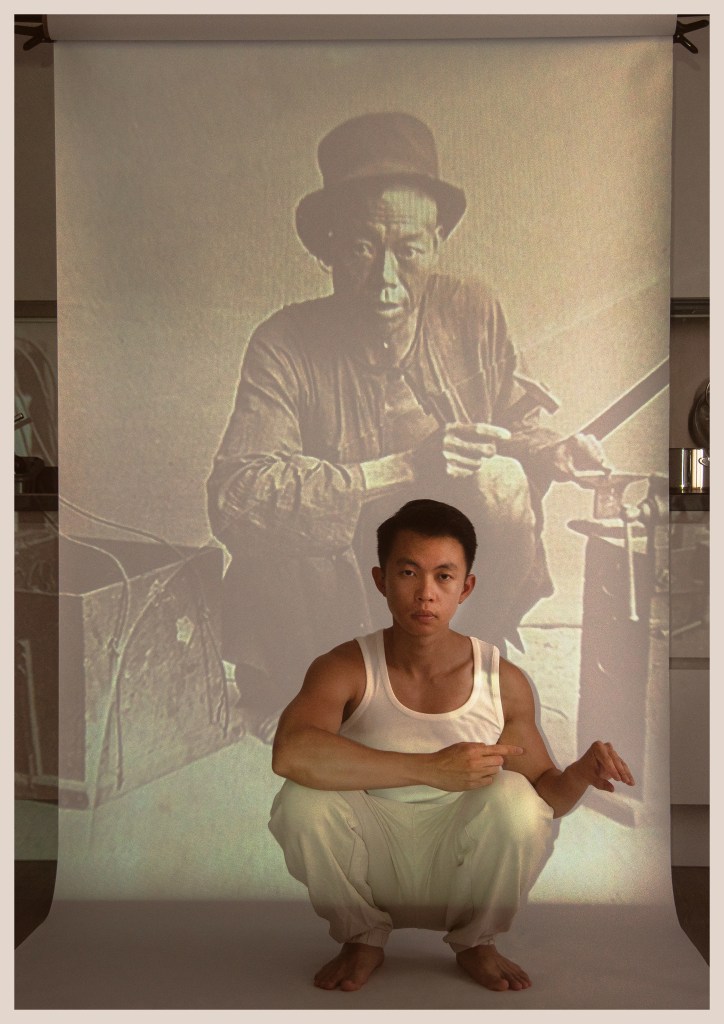

The first part of the Eastern Promise series employs a tripartite method of ‘archive-body-space’ superimposition: the artist enlarges images of Chinese laborers from colonial archives to life-size photographic backdrops, carefully staging scenes within his own residence — plants, furniture, textiles, and everyday objects compose a theatrical space imbued with the warmth of personal memory — then intervenes with their own body at this historical-contemporary interface. This creative methodology differs from other artists’ direct appropriation of archives or revival of traditional crafts; rather, through ‘bodily presence’, it transforms historical images into a material-spatial installation that can be re-experienced.

When the artist’s contemporary body encounters the historical body within the archive in a single frame, the unidirectionality of the colonial gaze is fundamentally shattered. This is not simple historical reenactment, but a form of ‘reverse anthropological study’ — the Chinese laborer’s body, once measured, classified, and gazed upon, now reclaims the power to gaze back through the artist’s active performance. The choice of a London apartment itself constitutes a critical geo-political metaphor: as a migrant from a former colony, the artist restages colonial archives within the private domain of the imperial center, an act that drags historical violence from public archives into personal everyday space, compelling viewers to re-examine colonialism’s enduring legacy within the tension between intimacy and estrangement.

The second part of the series focuses on ‘gesture studies’ of Chinese bodies in colonial archives. Unlike the spatial narrative of the first part, these images return to studio-style minimalist backgrounds, with the artist re-enacting the standardized bodily postures from the archives through different gestures. This strategy reveals how colonial photography, through the disciplining of gesture, transformed living individuals into visual data available for comparison and classification. Yet when these gestures are re-executed by a contemporary body, they are no longer passive submission but transformed into a ‘politics of gesture’ — each deliberate gaze back, each subtle deviation in posture, declares the return of subjectivity.

Sean Cham’s practice thus constitutes a distinctive ‘body-archive methodology’: not treating archives as historical heritage requiring protection, nor simply critiquing their violence, but through bodily material intervention, transforming the archive into an active space that can be re-entered, re-experienced, and rewritten. This methodology is deeply rooted in the dual positioning of Southeast Asian Chinese diasporic communities — both victims of colonial history and contemporary subjects who have regained voice at the imperial center. The work refuses to collapse perception into nostalgia or anger toward history, but through the triple weaving of body-space-image, within the tactile sense of material-history, collectively safeguards a mode of perception marked by justice, plurality, and the dignity of subjectivity.

He Yining, Curator of Guangzhou Image Triennial 2025

Exhibition at Saatchi Gallery, London, 2025

Photo: Matt Chung